Introduction

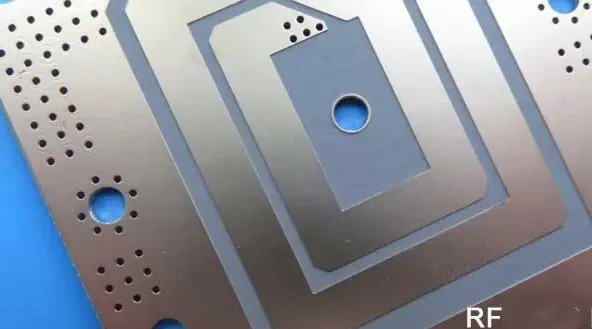

Taconic RF-35 is a popular high frequency laminate material designed for performance-driven RF PCB applications. With a dielectric constant of 3.5, low loss, and tight material uniformity, RF-35 enables excellent signal integrity for today’s high speed digital and analog circuits.

This article provides an in-depth look at RF-35 material properties, performance capabilities, design considerations, and applications. We’ll explore everything engineers need to know about specifying and working with this versatile RF material.

RF-35 Overview

Taconic RF-35 is a PTFE composite laminate comprised of:

- Woven fiberglass reinforcement

- Ceramic filler particles

- PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) resin system

With a dielectric constant of 3.5, it provides:

- Excellent high frequency signal performance

- Very low loss characteristics

- Tight dielectric constant tolerance

RF-35’s properties make it suitable for a wide range of radio frequency, microwave, millimeter-wave, and multi-gigabit digital applications. It strikes an optimal balance between cost and high frequency signal integrity.

Some key traits of Taconic RF-35 include:

- Dielectric constant of 3.5 +/- 0.05

- Low loss with tight uniformity

- Excellent thermal stability

- Good CTE for reliability

- Lead-free compatible

- US laminator source

- ITAR free

- RoHS compliant

- Cost-effectiveness

For designs from 10+ Gbps digital to Ku band RF, RF-35 delivers proven results across countless commercial and defense programs.

Material Properties

RF-35 is formulated from PTFE reinforced with ceramic particles to achieve:

Dielectric Constant – The k-value determines velocity of signal propagation and affects many circuit parameters. RF-35 provides an Er of 3.5 with very tight +/- 0.05 tolerance for consistent performance. This enables excellent impedance control compared to typical FR-4 (Er=4.5).

Loss Tangent – With a loss tangent of just 0.0019, RF-35 provides very low loss for high frequency energy. This maximizes Q factors in resonant circuits and insertion loss in transmission lines. Wide range of tested Dk from DC to Ku band.

Moisture Absorption – At just 0.02% moisture absorption, RF-35 resists detrimental effects of humidity and water ingress far better than conventional FR-4 material. This enhances long term reliability.

Thermal Performance – With a Z-axis CTE of 82 ppm/C, close PCB/laminate CTE matching reduces stresses under temperature cycling for excellent reliability. Good thermal conductivity (0.71 W/mK) spreads heat.

Lead-Free Assembly – RF-35 achieves high Tg (>280C) allowing compatibility with lead-free solder profiles of up to 260C for modern assembly.

Available Forms

RF-35 laminate allows flexibility through different standard offerings:

Copper Cladding

- 1⁄2, 1, and 2 oz ED copper foil

- Standard HTE copper and rolled copper available

- Double-sided cladding enables signal layers

Core Thicknesses

- From 0.005 inches to 0.125 inches

- Typical stackups use multiple 0.005″ cores

- Thicker cores provide rigidity when needed

Panel Sizes

- 18” x 24”, 18” x 36”, and 24” x 36” standard panels

- Custom panel sizes possible

- 106 and 1067 styles available

- Enables bonding multilayer board stackups

- Matching resin system

Rod and Plate

- For machined parts, spacers, and non-PCB applications

- Reduces PIM in RF assemblies

- Ideal for fixtures and testing

This range covers the needs of most RF-35 PCB implementations from prototyping to production.

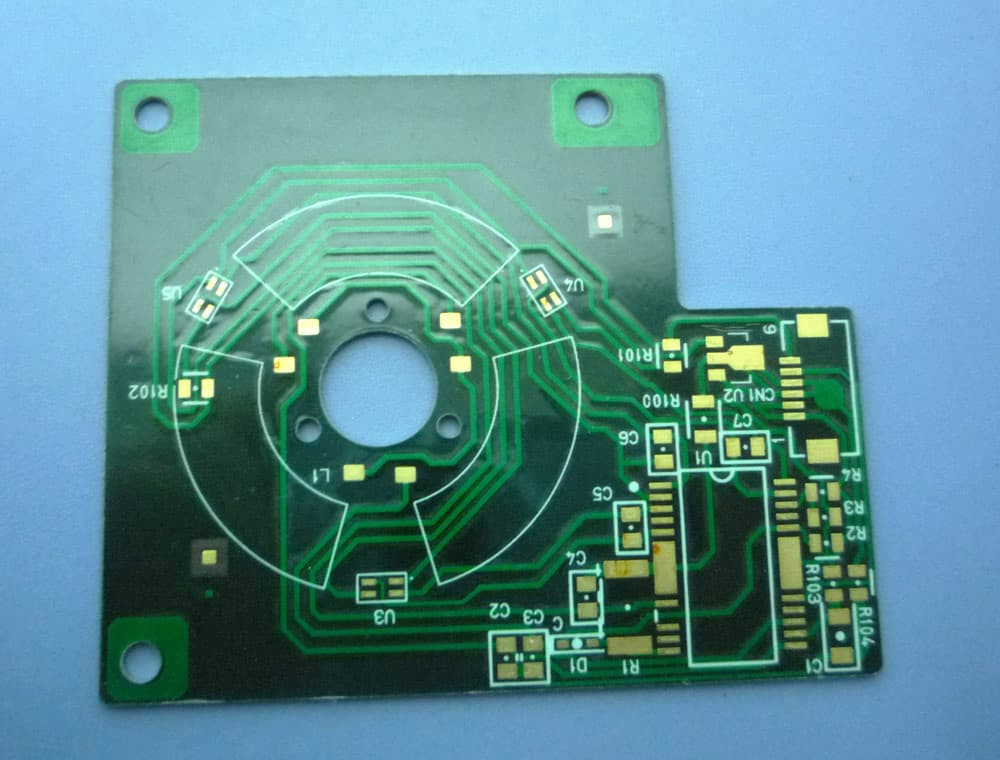

PCB Performance Capabilities

RF-35 laminate provides excellent RF and high speed digital performance when designed properly:

Frequency Range

- Usable continuous range from DC to Ku band (18 GHz)

- Material characterizations up to 40+ GHz

- Q factors exceeding 300 above 8 GHz

Loss

- Low loss tangent of 0.0019

- Insertion loss < 0.016 dB/inch at 20 GHz in 50Ω stripline

VSWR

- Tight dielectric constant tolerance enables excellent impedance control

- VSWR < 1.2 up to 15 GHz achievable

Propagation Delay

- Delay = 1.7 ns/inch typical at 50Ω

- Enables high data rates and rise time performance

Pulse Response

- TDR shows minimal discontinuities and reflections

- Clean time domain performance for ultra high-speed digital

Leveraging these attributes allows RF-35 PCBs to deliver highly repeatable RF and high speed digital operation.

Design Considerations

To obtain maximum benefit from RF-35 laminates, engineers should follow best design practices:

Stackup Planning

- Use multiple thinner cores instead of one thick core

- Alternating grain direction improves dimensional stability

- Model expected performance in solver

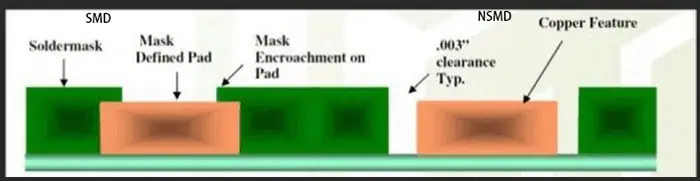

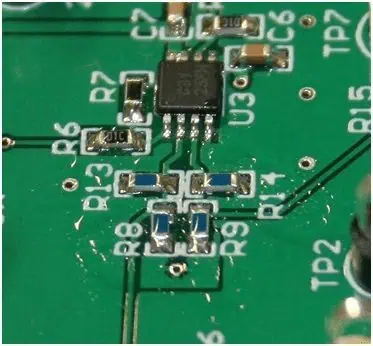

Impedance Control

- Leverage precise Er of 3.5 to maintain target impedance

- 50Ω striplines for RF and high-speed routing

- Controlled line width, dielectric height, trace geometry

Skin Effect

- Consider skin effect depth above ~ 8-10 GHz

- Utilize surface treatments like micro-etching

Signal Coupling

- Careful gap/spacing rules between traces

- Ground plane isolation techniques

- Avoid 90 ̊ bends; use arc/tapered geometries

Thermal Management

- Ensure sufficient thermal ground plane spreading

- Efficient component layout to avoid hotspots

- Consider thermal vias for heat transfer

Paying attention to these guidelines helps achieve first-pass PCB layout success with RF-35.

Recommended Stackups

Typical RF-35 PCB stackups may use configurations like:

- Multiple thin dielectric cores

- Signal routing on surface layers

- Dedicated ground planes near signals

- Buried capacitance within stackup

- Component cavities in ground planes

The thin cores and smooth copper foils of RF-35 enable tight impedance tolerance and high performance interconnects between ICs, filters, amplifiers, control logic, and other components.

Benefits vs. FR4

Compared to conventional FR-4 laminates, RF-35 provides:

Superior Loss Characteristics

- Lower loss tangent: 0.0019 vs 0.02 for FR-4

- Much flatter loss vs. frequency curve

- Maintains low loss to > 10 GHz

Tighter Dielectric Constant Tolerance

- Tolerance +/- 0.05 vs +/- 0.25 for FR-4

- Enables consistent impedance across PCBs

Improved Moisture Resistance

- 0.02% moisture absorption vs 0.2% for FR-4

- Far less susceptible to humidity effects

Higher Frequency Support

- Usable range to Ku band vs drop-off around 5 GHz with FR-4

- Significantly better Q factors at high microwave bands

For peak signal integrity at microwave and mmWave frequencies, RF-35 is a clear choice over FR-4 material.

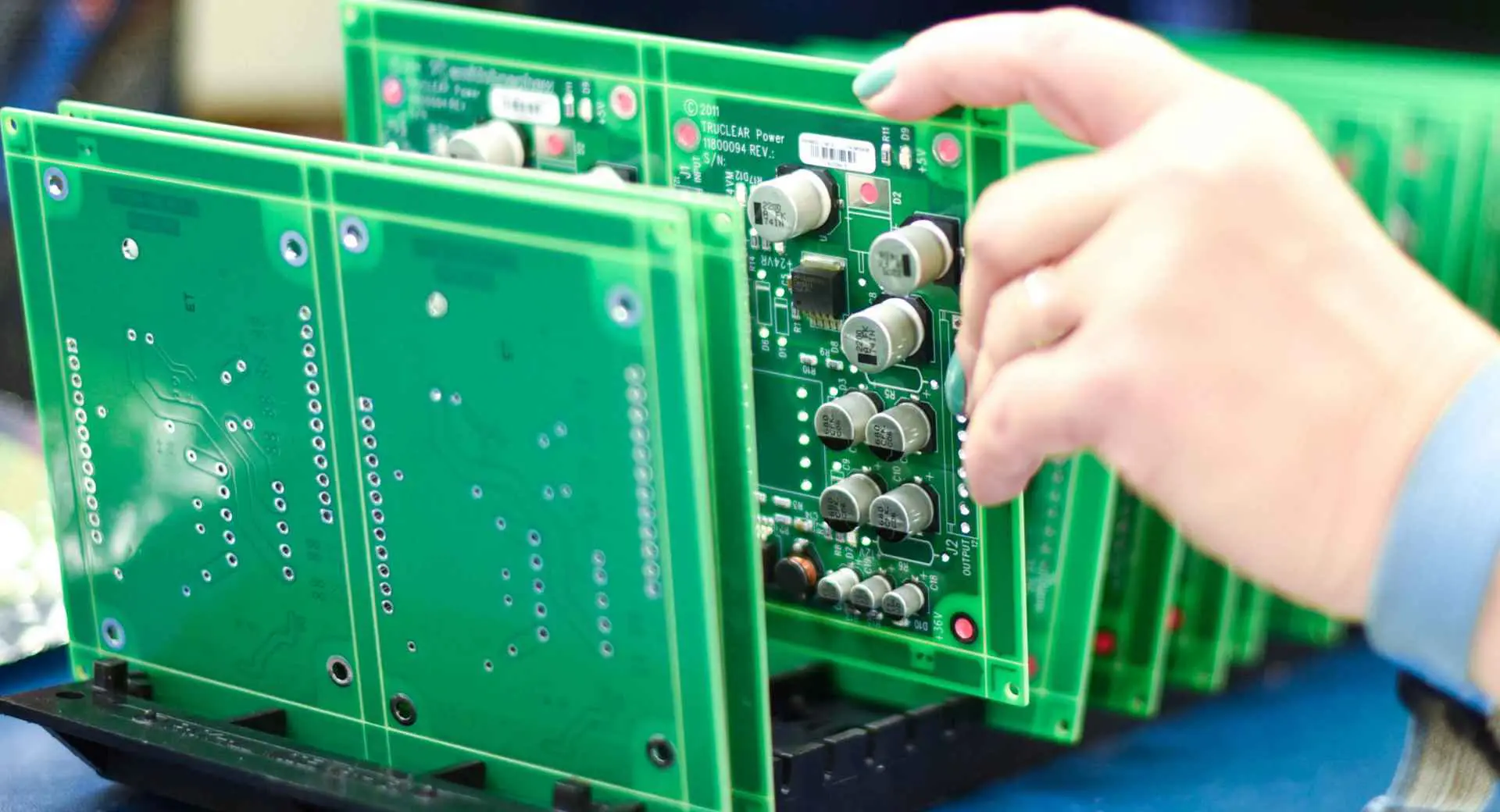

Typical RF-35 Applications

The capabilities of RF-35 make it a frequent choice for products including:

- Satellite communications

- Radar and remote sensing

- 5G telecom infrastructure

- Automotive radar

- Wireless networking

- Microwave radio/links

- Defense electronics

- Mobile devices

- High speed digital design

- Aerospace and avionics

Any application where optimizing signal integrity, reducing loss, and maintaining consistent performance over frequency are critical requirements will benefit from RF-35 PCB material.

Pros and Cons

Like any material, RF-35 has both advantages and disadvantages:

Pros

- Excellent high frequency signal integrity

- Low loss PTFE material

- Tight dielectric constant tolerance

- Lead-free assembly compatible

- Good thermal conductivity

- Reduced moisture absorption

Cons

- Higher cost than FR-4

- Lower flexural strength than glass-reinforced laminates

- Requires advanced fabrication processes

- Limited global supply chain

Conclusion

With its precise dielectric constant of 3.5 and low loss PTFE composition, Taconic RF-35 delivers proven performance for today’s emerging RF, microwave, and multi-gigabit digital designs. When engineered properly, RF-35 PCBs provide consistent behavior across fabrication lots and excellent high frequency response. For designers pursuing every last dB of loss or GHz of bandwidth, RF-35 remains an enabling material.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the key differences between RF-35 and common FR-4 laminates?

A: RF-35 provides much lower loss, tighter dielectric tolerance, lower moisture absorption, and extended high frequency range versus economical FR-4.

Q: What are some tips for working with thinner RF-35 cores?

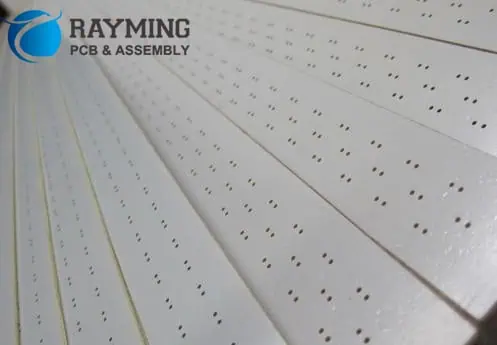

A: Use dedicated layer alignment equipment, employ smaller component sizes, plan sufficient panelization spacing, and minimize handling to avoid cracking thin cores.

Q: Does RF-35 require special PCB fabrication processes?

A: RF-35 benefits from advanced PTFE processes for via formation, hole walls, and drilling. It also requires lamination processes tailored to thinner cores.

Q: What are typical finished RF-35 PCB thicknesses?

A: High frequency designs aim for overall PCB thickness under 0.030 inches. This requires precision lamination of multiple 0.005 inch dielectric cores.

Q: Are there lead-free soldering implications with RF-35 material?

A: RF-35 achieves high Tg (>280C) for compatibility with lead-free profiles up to 260C peak temperatures. Thermal relief in multilayers is recommended.

Do you know RF-35 (TACONIC material)?

Performance:

(1) low cost;

(2) Excellent peel strength;

(3) Extraordinary low loss factor;

(4) low water absorption rate;

(5) Enhanced surface smoothness.

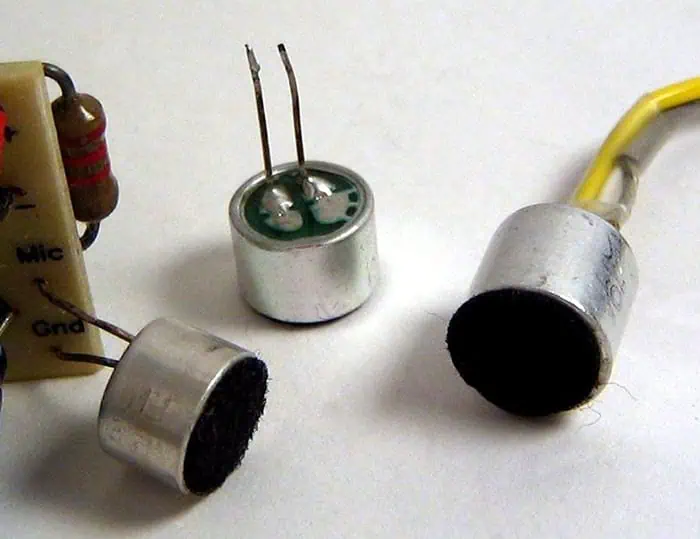

Application:

(1) power amplifier;

(2) filters and connectors;

(3) Passive components.

1)RF-35 is an organic-ceramic laminate material in the ORCER of TACONIC products.

2)It is a reinforced glass material based on woven glass cloth, and a combination of TACONIC’s ceramic filling technology and glass fiber coated PTFE technology.

3)RF-35 is the best choice for low cost, high volume commercial microwave and wireless frequency applications.

3)RF-35 of 1/20Z and 10Z copper foil boards, even with standard epoxy materials, have excellent peel strength and provide rework at any time.

4)The glass transition temperature of RF -35 exceeds 315 ℃.

5)The ultra-low water absorption and low loss factor of RF-35 minimizes phase shift in the frequency range of use.

6)The dimensional stability of RF-35 is due to the use of woven glass cloth in its design development.

7)RF-35 laminate material, generally with single or double-sided 1/20Z, 10Z and 20Z thickness of electrolytic copper foil. Different sizes of sheets can be selected according to requirements.

8)For the RF-35 microwave material, the relationship between the thermal expansion rate in the Z-axis direction and the temperature is shown in the figure below:

9)RF-35 dielectric constant changes with temperature:

10)RF-35 dielectric loss changes with temperature:

10)The relationship between the dielectric constant and frequency of RF-35 microwave materials is shown in the figure below:

11)The relationship between the dielectric loss of RF and the frequency of microwave materials is shown in the figure below: