Introduction

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) have emerged as the preferred platform for high-performance digital signal processing (DSP) applications, offering a unique combination of flexibility, parallelism, and performance that traditional processors cannot match. Among the most fundamental DSP operations implemented on FPGAs, Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filters represent a critical building block that demands careful attention to timing optimization. As data rates continue to increase and latency requirements become more stringent, timing-driven design strategies have become essential for achieving optimal performance in FPGA-based FIR filter implementations.

The challenge of timing optimization in FPGA-based FIR filters extends beyond simple clock frequency considerations. Modern applications require designers to balance multiple competing objectives: maximizing throughput, minimizing latency, reducing resource utilization, and maintaining numerical accuracy. This multifaceted optimization problem necessitates sophisticated design strategies that leverage both architectural insights and implementation techniques specific to FPGA platforms.

FIR Filter Fundamentals and FPGA Implementation Challenges

FIR filters perform convolution operations between input samples and a set of predetermined coefficients, producing output samples according to the equation:

y[n] = Σ(k=0 to N-1) h[k] × x[n-k]

Where y[n] is the output sample, h[k] represents the filter coefficients, x[n-k] are the delayed input samples, and N is the filter length. While conceptually straightforward, implementing this operation efficiently on FPGAs presents several timing-related challenges.

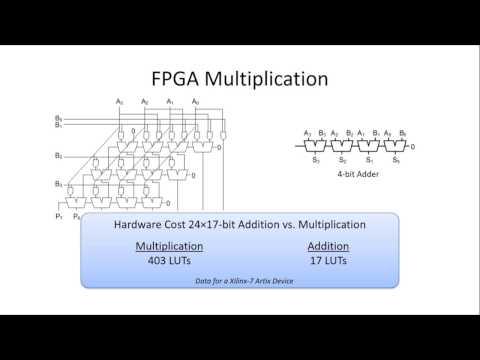

The primary timing bottleneck in FIR filter implementations arises from the accumulation path, where partial products must be summed sequentially. In a naive implementation, the critical path would span multiple adder stages, limiting the achievable clock frequency. Additionally, the multiplication operations between input samples and coefficients can introduce significant propagation delays, particularly when using embedded multiplier blocks that may not be optimally placed relative to other logic elements.

FPGA-specific considerations further complicate timing optimization. Unlike ASICs, FPGAs have heterogeneous resources including dedicated DSP blocks, block RAMs, and configurable logic blocks, each with distinct timing characteristics. The routing architecture, while flexible, introduces variable delays that depend on the physical placement of logic elements. These factors necessitate design strategies that account for both algorithmic efficiency and platform-specific implementation details.

Architectural Design Strategies for Timing Optimization

Pipelining Techniques

Pipelining represents the most fundamental strategy for improving timing performance in FPGA-based FIR filters. By inserting registers at appropriate points in the datapath, designers can break long combinational paths into shorter segments, enabling higher clock frequencies. However, effective pipelining requires careful analysis of the computation structure to identify optimal pipeline boundaries.

Deep pipelining strategies involve inserting registers within individual multiply-accumulate operations, creating fine-grained pipeline stages. This approach is particularly effective for high-order filters where the accumulation chain would otherwise dominate the critical path. The trade-off is increased latency and register utilization, which must be balanced against the timing benefits.

Retiming techniques can further optimize pipelined implementations by redistributing registers to achieve better timing balance across pipeline stages. Modern synthesis tools provide automated retiming capabilities, but manual intervention is often necessary to achieve optimal results, particularly when dealing with complex filter structures or resource constraints.

Parallel Processing Architectures

Parallel processing offers another powerful approach to timing optimization, particularly for applications with high throughput requirements. The most common parallel architectures for FIR filters include:

Transposed Direct Form: This architecture parallelizes the multiply-accumulate operations by implementing them as separate multiply-add chains. Each coefficient multiplication occurs in parallel, with the results combined through a tree of adders. This approach eliminates the sequential accumulation bottleneck but requires additional multiplier resources.

Polyphase Decomposition: For decimation or interpolation filters, polyphase decomposition allows the filter to be partitioned into multiple parallel sub-filters operating at reduced sample rates. This technique not only improves timing by reducing the effective computation rate but also enables efficient resource utilization through time-multiplexing.

Systolic Array Implementations: Systolic arrays provide a highly regular architecture suitable for FPGA implementation. These structures feature short, identical connections between processing elements, enabling predictable timing characteristics and efficient routing utilization.

Coefficient Optimization Strategies

The choice and representation of filter coefficients significantly impact timing performance. Several optimization strategies can be employed:

Canonical Signed Digit (CSD) Representation: CSD encoding minimizes the number of non-zero digits in coefficient representation, reducing the complexity of multiplier implementations. This technique is particularly beneficial when implementing multipliers using shift-and-add structures rather than dedicated DSP blocks.

Coefficient Symmetry Exploitation: Many FIR filters exhibit symmetric or anti-symmetric coefficient patterns. Exploiting this symmetry can reduce the number of required multiplications by approximately half, with minimal timing overhead for the additional summation operations.

Dynamic Range Optimization: Analyzing the dynamic range requirements of intermediate computations allows for word-length optimization that can improve timing by reducing multiplier and adder complexities while maintaining acceptable numerical performance.

Implementation-Level Timing Optimization

Resource Mapping and Allocation

Effective utilization of FPGA resources is crucial for achieving optimal timing performance. Modern FPGAs provide dedicated DSP blocks optimized for multiply-accumulate operations, offering superior timing characteristics compared to equivalent implementations using general-purpose logic. However, these resources are limited and must be allocated judiciously.

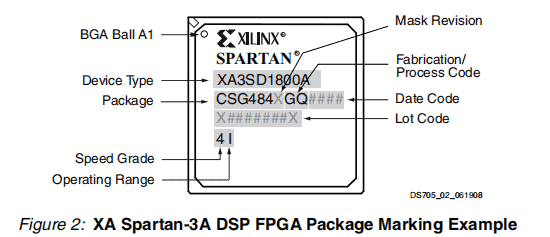

The mapping of filter operations to DSP blocks requires consideration of the specific architecture of the target FPGA. For example, modern Xilinx UltraScale+ devices provide DSP48E2 blocks capable of performing complex multiply-accumulate operations with built-in pre-adders and post-adders. Utilizing these features effectively can eliminate additional logic requirements and improve overall timing.

Block RAM utilization for coefficient storage and delay line implementation also impacts timing performance. The timing characteristics of block RAMs depend on their configuration and access patterns. Optimizing these parameters while considering the overall system timing requirements is essential for achieving optimal performance.

Floorplanning and Placement Optimization

Physical placement of logic elements significantly affects timing performance in FPGA implementations. The routing delays between components can vary substantially based on their relative positions on the device. Strategic floorplanning can minimize these delays and improve timing predictability.

Clustering related logic elements in proximity reduces routing delays and improves timing closure. For FIR filter implementations, this typically involves grouping multiply-accumulate operations and their associated control logic within local regions of the FPGA. Advanced placement constraints can guide synthesis and place-and-route tools to achieve better results.

Regional clock buffering strategies can also impact timing performance, particularly in large filter implementations that span significant portions of the FPGA fabric. Careful consideration of clock distribution and skew management ensures reliable operation at high frequencies.

Advanced Timing Closure Techniques

When standard optimization techniques are insufficient to meet timing requirements, advanced closure strategies may be necessary:

Multi-Cycle Path Constraints: Some signal paths in FIR filter implementations may not require single-cycle timing, particularly in control or configuration paths. Identifying and constraining these paths appropriately prevents them from limiting overall performance.

False Path Analysis: Complex filter implementations may contain logic paths that are never exercised during normal operation. Identifying and constraining these false paths eliminates unnecessary timing restrictions.

Clock Domain Crossing Optimization: Multi-rate filter implementations often require careful management of clock domain crossings. Proper synchronization techniques and timing constraints ensure reliable data transfer while minimizing impact on overall performance.

Case Studies and Performance Analysis

Practical implementation of timing-driven FIR filter design strategies demonstrates their effectiveness across various application scenarios. Consider a 128-tap FIR filter targeting a Xilinx UltraScale+ FPGA with a 500 MHz operating frequency requirement.

A baseline direct-form implementation typically achieves approximately 200 MHz due to the long accumulation chain. Applying deep pipelining with 8 pipeline stages improves performance to 350 MHz but increases latency to 8 clock cycles. Further optimization through transposed direct-form architecture with coefficient optimization achieves the target 500 MHz frequency while reducing latency to 3 cycles.

Resource utilization analysis reveals trade-offs between timing performance and implementation efficiency. The optimized implementation requires 64 DSP blocks compared to 128 in the baseline, demonstrating the effectiveness of architectural optimization in achieving better resource efficiency alongside improved timing.

Power consumption analysis shows that timing-optimized implementations often consume less power despite higher operating frequencies, due to reduced logic depth and improved resource utilization efficiency.

Future Directions and Emerging Techniques

Emerging FPGA architectures continue to evolve, offering new opportunities for timing optimization. AI-enhanced design tools are beginning to provide automated optimization capabilities that can identify non-obvious timing improvement opportunities. Machine learning approaches to placement optimization show promise for achieving better timing closure with reduced manual intervention.

Adaptive filter implementations that can modify their characteristics in real-time present new timing challenges and opportunities. These systems require careful consideration of reconfiguration timing and the impact of dynamic parameter changes on overall system timing.

Conclusion

Timing-driven FIR filter design for FPGAs requires a comprehensive approach that spans algorithmic optimization, architectural design, and implementation-level techniques. Success depends on understanding the interplay between filter requirements, FPGA resource characteristics, and timing constraints. As FPGA capabilities continue to advance and application requirements become more demanding, these design strategies will remain essential for achieving optimal performance in high-speed DSP applications.

The evolution toward more sophisticated timing optimization techniques, combined with improved design tools and methodologies, promises to further enhance the capabilities of FPGA-based DSP systems. Designers who master these timing-driven strategies will be well-positioned to leverage the full potential of FPGA platforms for next-generation signal processing applications.

Related posts:

- Strategies to the Design of Crosstalk between Two Parallel Micro-strip Lines on PCB Based on the Simulation Analysis

- Active Filter Vs Passive Filter: What’s the Difference?

- Problems of EMC Technology Application in PCB Design of Electronic Devices and the Strategies

- Low Pass Filter: Types, Applications, and Design Guide [2025]