Bend Radius Calculator (IPC-2223)

IPC-2223 Bend Radius Guidelines

Quick Tip

For dynamic applications, always use RA copper and minimize thickness. Thinner = tighter bends + longer flex life.

Bend Ratio Table (IPC-2223)

| Application | Layers | Ratio (r/h) |

|---|---|---|

| Static | 1-2 | 6:1 |

| Static | 3+ | 12:1 |

| Dynamic | 1 | 100:1 |

| Dynamic | 2 | 150:1 |

| Dynamic | 3+ | 200:1 |

Design Warnings

- Never place vias in bend areas

- Route traces perpendicular to bend axis

- Use hatched ground planes in flex zones

- ED copper NOT recommended for dynamic

- Add 20% safety margin to calculations

Stack-Up Configuration

Stack-Up Visualization

Flexible PCB Material Comparison

Selection Guide

Choose Polyimide (PI) for most applications. PET for low-cost/low-temp only. LCP for high-frequency/harsh environments.

Polyimide (PI)

Polyester (PET)

LCP

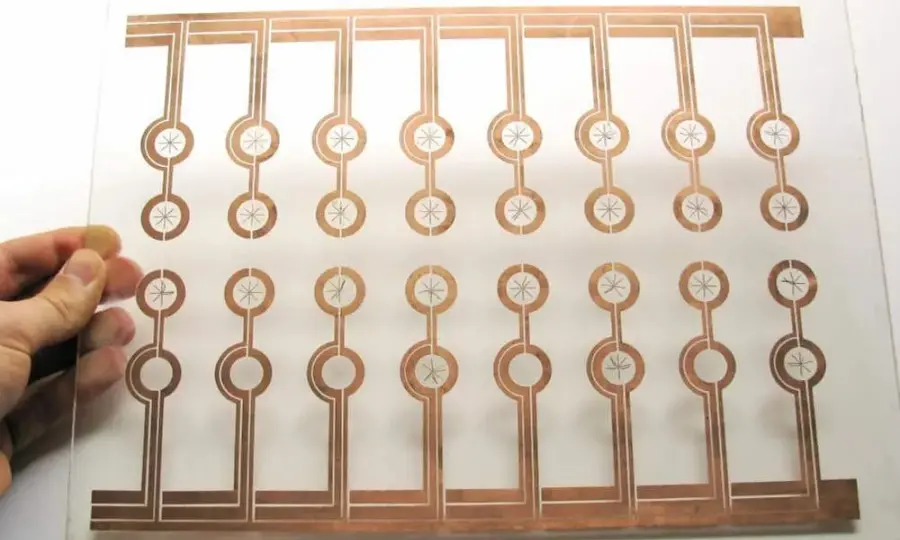

Copper Foil: RA vs ED

| Property | RA Copper | ED Copper |

|---|---|---|

| Grain | Horizontal | Columnar |

| Elongation | 20-45% | 4-10% |

| Flex Life | Excellent | Limited |

| Cost | +20-30% | Baseline |

| Best For | Dynamic Flex | Static Flex |

Coverlay vs Flex Solder Mask

| Property | PI Coverlay | Flex Mask |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Polyimide film | Photo-imageable |

| Flexibility | Excellent | Good |

| Opening Tol. | ±0.15mm | ±0.05mm |

| Dynamic Flex | Required | No |

| Cost | Higher | Lower |

Flexible PCB Cost Estimator

Cost Breakdown

Estimated Total

$127

$1.27 per unit

Note

Rough estimate only. Contact RayPCB for accurate quotes.

Flex PCB Design Rules

| Parameter | Standard | Advanced |

|---|---|---|

| Min Trace Width | 0.1mm (4mil) | 0.05mm (2mil) |

| Min Spacing | 0.1mm (4mil) | 0.05mm (2mil) |

| Min Drill | 0.2mm | 0.1mm |

| Annular Ring | 0.15mm | 0.1mm |

| Coverlay Opening | ±0.15mm | ±0.1mm |

| Registration | ±0.1mm | ±0.05mm |

| Impedance Tol. | ±10% | ±5% |

Routing Guidelines

DO

- Route traces perpendicular to bend

- Use curved traces (no sharp corners)

- Distribute traces evenly

- Use hatched ground planes

- Add teardrop pad entries

DON'T

- Place vias in bend areas

- Route parallel to bend axis

- Use 90° corners

- Use solid copper pours in flex

- Place components near flex edge

IPC Standards Reference

| Standard | Title | Application |

|---|---|---|

| IPC-2223 | Sectional Design Standard for FPBs | Primary design guide |

| IPC-6013 | Performance Specification for FPBs | Acceptance criteria |

| IPC-4202 | Flexible Base Dielectrics | Material specs |

| IPC-4203 | Cover Sheets Specification | Coverlay specs |

| IPC-A-600 | Acceptability of Printed Boards | Visual standards |

Unit Conversions

| Length | Conversion |

|---|---|

| 1 mil | = 25.4 μm = 0.001 inch |

| 1 μm | = 0.0394 mil |

| 1 mm | = 39.37 mil = 1000 μm |

| Copper Weight | Thickness |

|---|---|

| 1/4 oz | 9 μm (0.35 mil) |

| 1/3 oz | 12 μm (0.47 mil) |

| 1/2 oz | 18 μm (0.7 mil) |

| 1 oz | 35 μm (1.4 mil) |

| 2 oz | 70 μm (2.8 mil) |

PI Temp Limit

Survives lead-free reflow (260°C)

Dielectric (PI)

At 1 MHz frequency

Dynamic Life

With RA copper + proper design

Min Thickness

Single-layer with thin materials

Moisture (PI)

Bake 120°C/4hrs before solder

Elongation

vs ED copper 4-10%